This is my first story on the forum, so I hope it's entertaining to at least a few of you, and that I've followed all of the rules, etc. I will absolutely welcome any and all criticism or suggestions. A lot of you have been doing this much longer than I have, and I'm sure I could benefit from any advice you would be willing to give.

One quick note: by coincidence, most of the screenshots for this first installment are taken from the distance, so you don't see many faces. I'm sure this stems in large part from the fact that I am a builder at heart, so doing a story is a very new kind of gameplay for me. Fear not - the main characters will become more clear in the next chapter. I'm slowly but surely letting go of my micromanaging style, and my attachment to pretty scenery.

Anyway -- On to the story!

---------

CHAPTER ONE - The Island (scroll down in this post)

CHAPTER TWO - SavnaCHAPTER THREE - FatherCHAPTER FOUR - UnpackingCHAPTER FIVE - CourtyardCHAPTER SIX - TavernCHAPTER SEVEN - StableCHAPTER EIGHT - RootCHAPTER NINE - BoatCHAPTER TEN - StellanCHAPTER ELEVEN - Dining RoomCHAPTER TWELVE - Locked UpCHAPTER THIRTEEN - PlansCHAPTER FOURTEEN - EscapeCHAPTER FIFTEEN - LawCHAPTER SIXTEEN - WeddingCHAPTER SEVENTEEN - AnnouncementCHAPTER EIGHTEEN - AjianaCHAPTER NINETEEN - They KnowCHAPTER TWENTY - The Other SideCHAPTER TWENTY-ONE - Market DayCHAPTER TWENTY-TWO - Laying the GroundworkCHAPTER TWENTY-THREE - ReunionCHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR - Building BlocksCHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE - Moon DialCHAPTER TWENTY-SIX - OpenCHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN - SadnessCHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT - GoneCHAPTER TWENTY-NINE - JournalCHAPTER THIRTY - PeninsulaCHAPTER THIRTY-ONE - RadalCHAPTER THIRTY-TWO - Mara---------

A young woman sits a an ornate wooden desk, writing on the first page of a leatherbound, blank journal...Where to begin? I suppose I should start by telling you about my home, and the way it's changed. When I was growing up, we always called it Ajri, which just meant "the land." There was no other place but the water, which surrounded the land on all sides, and, as far as we knew, went on and on to the end of creation.

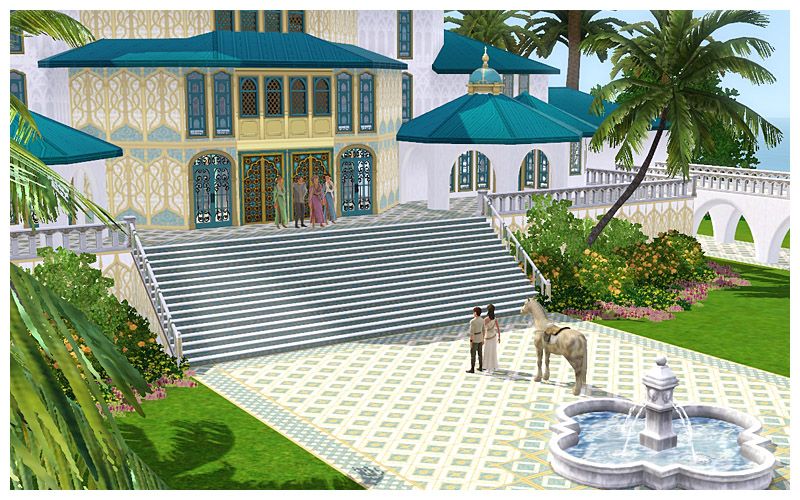

Ajri is a beautiful place. The sun always shines, except when light showers rain down on the trees and grass, to keep them green. Soft breezes blow in across the ocean, scented with the flowers they rustle along the coast. Our legends and myths and ancient texts contain other words for the island, used in stories or by peoples long ago forgotten: Elysium. Avalon. Tir na Nog. Valinor.

The list is long, but all of the stories talk of paradise; a place of eternal youth and beauty where music, joy, abundance of life, and all pleasurable pursuits come together in a single place. Where happiness lasts forever, and sickness and death simply do not exist.

To those who actually live here, though, our lives were a collection of simple pursuits, lived in the same way they had been lived for as long as any could remember. And our paradise was built, not a gift from some greater gods.

The Nelayan family lived in small fishing villages all along the coast, and were the best sailors and boatwrights on the island. Their houses were small and simple, but their people were well-respected – even revered – as the Ones Who Provide Food. Ajri provided all of us with fruits and herbs for the taking, but the Nelayan hauled in great nets full of fish, brought baskets of clams and oysters up from the ocean's floor, and provided us all with shrimp, and lobster and the other fruits of the sea. They also farmed grains and vegetables, hunted for game, and raised small animals for milk and cheese, or for eggs. Without their labor, we would have all spent our days toiling away for subsistence, and our society would never have developed into anything greater.

Our progress was reflected in the name of the Pembina family, which originally meant simply "the Ones Who Provide Shelter." But their craftsmanship extended far beyond simple housing. It's true that they built beautiful buildings. Their stonemasons, glaziers, blacksmiths, carpenters and woodcarvers were clever and highly skilled, and could build fantastical structures that rose up higher than the trees. But they also carved beautiful windowscreens, and built sturdy furniture. They made wagons and carts, barrels and bottles, knives and horseshoes, guitars and drums, pots and pans and sinks and tubs. It seemed that in all cases, if something needed to be manufactured, their craftsmen could conceive a solution, and then produce it from their busy and inventive workshops. Anything practical or mechanical was within their purview, and they never disappointed.

Both families traded often with the jah'Itan – the Ones Who Provide Clothing – whose weavers made fabric of all kinds, from sturdy sailcloth, to delicate veiling, to richly colored brocades and damasks. The jah'Itan were also the jewelers of the island, working pearls found by the Nelayan divers or gems found by the Pembina miners into necklaces, bracelets, earrings and headbands of surpassing beauty. Just as the Pembina were concerned with everything practical, the jah'Itan made it their business to produce or procure any fanciful item you could imagine, and some you could not. They made feathered jackets and embossed boots, embroidered belts and lace veils. They were enthusiastic traders of all manner of goods, and their market days were not to be missed. Everyone came from all over Ajri to barter, buy and sell everything from fruit pies and small simple toys to elaborate dresses, painted carriages and exotic birds.

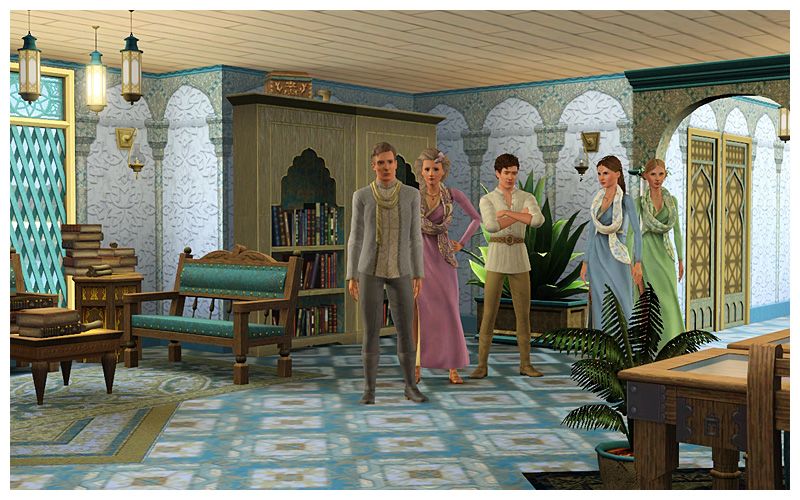

My family had few tangible things to trade – the items we crafted we always gave away, and the items we needed were given to us when needed – so we mostly came to the markets for news and entertainment. The reason we were so well provided for was because we are the den'Rhelys, which means... Actually, it's difficult to explain. It's nothing so straightforward as providing shelter or food or clothing. Den'Rhelys literally means "the Ones Who Know." And indeed, we started as teachers, and have always been teachers. But we do more than instruct. We produce medicines and laws, we catalogue plants and animals, create art and music, research new sciences and magics and record them all for future generations. The builders were busy with building, the sewers with sewing and the fishers with fishing. But the den'Rhelys were able to devote our time and effort fully to the cooperative pursuit of knowledge. We had time to make discoveries, explore their applications, and share them with any who could use them.

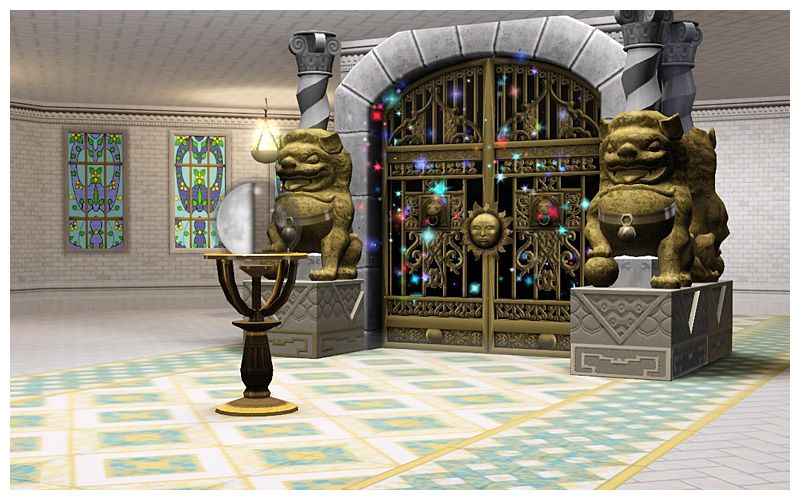

Most importantly, though, the den'Rhelys were -- and still are -- the Keepers of the Gate. And the Gate is what kept Ajri safe from all of the evils that dwelled in other worlds. We had built it, or our forefathers had, in ages long past. It was locked with a seal that looked like the sun, and guarded by a pedstal that contained the light of the moon. I don't claim to understand how it was locked -- I couldn't stand to be in the room with it. From the rear, the gate appeared to be standing freely in the center of the room, offering a clear view to the other side. But from the front, it led into utter blackness, and a cold, cold breeze blew through its grilled portal.

Luckily, my mother and father and a few other very wise scholars looked after the gate. My siblings and I were not yet needed or learned enough to be its guardians. We were of an age to travel to the other families to live with them, to teach their children the basics, like reading, writing, history and mathematics. While there, we were also tasked with learning skills and crafts, facilitating communication between the families and workshops on Ajri, and most importantly, looking for any students with particular talents that should be cultivated for the good of all of us. If we found such students, my father and a group of scholars would come to meet the child and, if the student were selected, my father would request that the family let the child go back with him for further education, and to become one of the scholars who lived and worked at our library. It was considered the highest honor to be chosen. No one ever refused.

When I was younger, I went to the jah'Itan. I learned the arts of weaving and jewelry making, and taught their youngest children their lessons. I sent regular reports back to my father, detailing the new ideas and processes that the Pembina had developed, disputes that needed resolution, or problems to be overcome, and he shared the reports with the scholars who might be interested or helpful. I also found a boy whose instinctive understanding of higher mathematics would have been wasted on bookkeeping for his family.

My sister Nellaska lived with the Nelayan, who taught her to fish and farm, to track and hunt, and to respect the balance of the water and the land. She found a young girl whose innate curiosity about plants had already led to the discovery of several new uses, as well a skilled young artist whose ability to paint and sculpt would have been limited in a family who spent most of their time on the water.

My brother Jaffaran lived with the Pembina, and -- well. I don't criticize my brother's learning or his dedication to Ajri. Jaffaran was as much a scholar as the rest of us, and I would never suggest that he would fail to do his duty. Especially not now. But to understand my brother, you must understand how much delight he took in the pleasures that Ajri offered. The den'Bruhal had sometimes been criticized, fairly or not, for a sense of superiority. We were said to be as aloof and as distant as our marble city on the island's highest peak, detached from the rest of the island, and from day to day life itself. But Jaffaran was different. He spent a good deal of his time among the Pembina carousing with the miners, teaching rude songs to the stonemasons, and riding his horse all over the countryside with friends for-- as he always justified it-- research purposes. It meant he became a part of his new home much more fully than Nellaska and I became part of ours. The Pembina loved him for it.

As I said, I wouldn't criticize my brother. In the midst of all of his "outside research," he taught their chidren well, and he learned a good deal about building.

It was his identification of local scholars, however, that led my father to question his work with the Pembina. Especially the one he brought home with him.